In the early days of the 21st century we literally have a problem. It’s the use – or, more to the point, the misuse – of the word literally.

In the early days of the 21st century we literally have a problem. It’s the use – or, more to the point, the misuse – of the word literally.

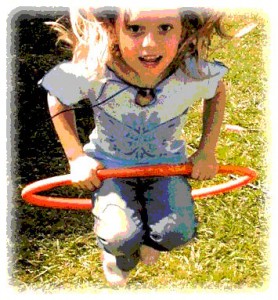

According to a spokesperson for a well-known clothing retailer, a new range of sweaters has been ‘literally flying out the door’. A woman named Tracey had to ‘literally jump through hoops’ to get a job. (And, no, the job in question was not with a circus.) While another woman – also named Tracey – ‘literally died’ when she discovered that she had won a competition organised by her local radio station.

Most careful users of language would agree that literal means something like: using words in their usual or primary sense, without metaphor or allegory.

You might be tempted to say: Well, so what? Any normal reader will realise that the sweaters did not really fly out the door on mysterious wings. Tracey Number One did not really jump through hoops. And Tracey Number Two did not really die. To object to the use of literally in these three examples is just out-dated pedantry. But is it?

It is hard to think of another single word that can substitute for literally. Exactly, precisely, really, truly … these all go part of the way. But when you literally mean literally, literally is probably the only word there is. And it’s certainly the best word there is.

Misusing it will, in time, rob us of a very useful word. So, it’s literally time to stop misusing literally.