It was a bitterly cold winter’s day. The wind was blowing straight from the Pole and every few minutes or so there was another shower of sleet.

It was a bitterly cold winter’s day. The wind was blowing straight from the Pole and every few minutes or so there was another shower of sleet.

A university don – the collar of his overcoat turned high, the brim of his hat pulled low – was walking along the street and, as he passed the recessed doorway of a closed shop, a scruffy chap – bare-headed and wearing a threadbare jacket – reached out a grimy hand and asked plaintively if the don would lend him some spare change.

The don paused briefly, looked down his nose at the unfortunate fellow, and then said, sonorously: ‘To quote the great William Shakespeare: “Neither a borrower nor a lender be.”’

As the don resumed his journey, the beggar called after him: ‘And to quote the great D H Lawrence: “Bastard!”’

I think it was my late brother-in-law who first suggested to me that if you want to add gravitas to something commonplace – or just something commonsensical – attribute it to someone famous. ‘Few people will argue with the words of Shakespeare, or Churchill, or Ionesco,’ he said. (I think he was writing a paper on Ionesco at the time.)

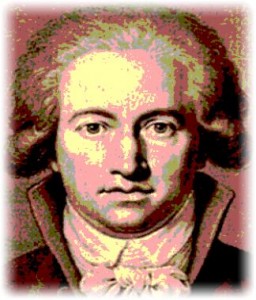

And so, when someone tells me that they are having trouble writing something clearly and concisely, I have often found it useful to quote Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

‘If any man wishes to write in a clear style, let him first be clear in his thoughts.’

Of course, I have no idea whether or not Goethe actually said this. And, even if he did, it seems rather unlikely that he would have said it in English. But it does make a lot of sense.